This week in 52 Stories: The Human Claim by Ali Smith. You can find it in the collection Public Library and Other Stories published by Penguin. Also Liberty published it online.

Some years ago I worked for a large US company in Silicon Valley. Eventually, I moved away from the sun and from America, but I kept the job for a year while I put myself through some more school. Every six weeks or so, I stuffed some clothes and a laptop into a backpack and flew out to San Francisco to work at the office for a couple of weeks.

The way I miss California sometimes is a kind of pain. It’s like exile – except, I remind myself, I have no right to that. I never belonged there. If I belong anywhere it’s – reluctantly – here in England. When I returned, I told myself: at least there’s Europe – I am still part of something diverse and exciting and huge. It’s not so bad.

Thinking of that time, it’s not just the palm prickling wait for the airport immigration interview I remember, or the moment of release into a half-abandoned SFO terminal, or the nice pavement slab thump of the hire car journey to San Francisco or Mountain View – the drum beat rumble over road segments that seem bolted together.

Almost as often, I return to that in-between stage – the sloughing off of who I was in England – the becoming a traveler. The cheapest flights left Heathrow early and I lived in the North, so it made sense to journey down to Heathrow the day before and to stay overnight. Usually, I found a deal online and ended up at a hotel on Bath Road – a dual carriageway that glances off the airport on its way in to London. I would buy a couple of bottles of beer and watch downloaded TV on my laptop. Sometimes I ran along a stretch of the road alongside concrete hotels, bunker-like McDonalds’ on one side and relentless traffic on the other. Even at my most surveilled – betrayed by my passport, and credit cards, and tracked by a thousand security cameras, I felt anonymous.

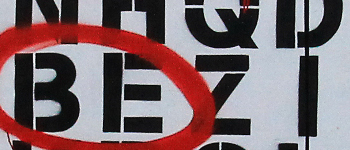

I was standing at the bus stop on the morning of a flight. Over several trips I had learned that the shuttle the hotels charged for was a con – I could get a free ride by just walking out into the street and stepping onto a regular red London bus. As I waited, my security check adrenalin was already pulling me taut. Then I saw a camera tripod-mounted above a shiny liveried car. Google caught me – and they put me on the map.

The Human Claim concerns a story Ali Smith intended to write – probably the one we actually read – about DH Lawrence, and about his ashes. It also describes narrator-Smith’s attempts to get fraudulent payments removed from her credit card account.

One theme, very relevant now – as Trump trumps away about fictitious wiretaps – concerns observation and the darkly comic imperfections of gathered intelligence. Lawrence, an anti-militarist in wartime and married to a foreigner, was hounded by the authorities. When the police raided his cottage, a Hebridean song was mistaken for code, sketches of plants taken for maps.

By the same token here in the now, the records of the narrator’s spending history – including her supposed purchase of an airline ticket from Lufthansa – are scrutinised by her credit card company. They find life as she lived it is less convincing than the entries on their computer system.

The story is filled with instances of relationships at a distance – mediated by imagination or assumption. After Lawrence’s death, Frieda Lawrence dispatched Ravalgi, her new husband, to exhume and cremate his body and to return with his ashes. Later, Ravalgi claimed that he dumped them as he made his way home. Sifting whatever it was he handed over (though I don’t know if she actually sifted anything), Frieda must have imagined a story in which her bidding was done. That version of the truth co-exists now with another in which the ashes were discarded and a third in which Ravalgi remained true to his task but nonetheless cared enough to lie about the matter – committing the sin at least in his imagination and in the eyes of others.

Ali Smith imagines her identity thief, a shadow version of herself, boarding the stolen Lufthansa flight.

Dec 21. Maybe this other me had been going home for Christmas. Did she have a family? Did the family know she was a fraudster? I could see them all round long table set for Christmas; I stood ghost at their feast and watched them with their arms around their shoulders as Hogmanay gave way to New Year.

As the thought resolves, the identity thief solidifies and the narrator fades – a phantom at the thievery feast. Meanwhile, the credit card company renders her impotent, makes her invisible.

A character in Lawrence’s novel St Mawr looks up at the ‘buzz rattled’ sound of a plane above. Near and far. An individual and imagined stories.

Often these relationships of distance and fracture illustrate the tension between the individual – the narrator, the reader, Lawrence – and exterior monolithic forces. We are set at odds with a big picture in which we barely figure. Have you noticed how often the numbers on offer in the call centre menu, the keep-inside-the-lines character boxes on the computer scannable immigration form, just don’t apply to you?

Short stories often hinge on a particular beat or image. In a modern tale this might take the form of a little nuanced shift rather than a striking moment of revelation. In this case, layered though the story is – with Ali Smith the person and Ali Smith the narrator, the story intended and the story before us (which may or may not be the same text), the tale of the credit card fraud in parallel with Lawrence’s life and writings – despite all that layering, there is a perfect turning point – an honest to goodness epiphany. Go, Ali Smith!

It is an accidental connection that draws it all together for Smith the narrator – she finds the Lufthansa offices on Bath Road just a short trip on Google’s street view to Harmondsworth, the home of Penguin and of Lawrence’s books (and those of Katherine Mansfield, whose life and opinions also peek briefly into this story).

“It was a ridiculous, glorious connection, and one that somehow made me bigger and than any false claim being made against me. It also made me laugh. I laughed out loud. I did a little dance around the room.”

My own epiphany, though, came to me shortly before the narrator’s dance as she inspects Bath Road on her computer screen.

“The photos on Google Street View had been taken in the early summer; the trees were leafy and the may was in bloom on the low dual carriageway bushes outside the Holiday Inn. At one point you could see right inside people’s cars. Google Street View had protected privacy by pixellating the numberplates of the cars. But at one point two cars were level at a junction and a man was in one, a woman in the other, and a lone pedestrian was waiting behind them at a bus stop. It was good to see some people coinciding, even unknowingly, just going somewhere one day, caught by a surveillance car and immortalized online […] Seeing them made me wonder briefly what was happening in their lives on the day this picture was taken. I wondered what that happened to them since. I hoped they’d been okay in the recession. I hoped they’d arrived safely wherever they were going.”

And then I performed my own figurative dance. There was, after all, a remote a chance that I was the figure at the bus stop and, if so, I joined the story there.

They let me through security and I waited in the departure lounge, worrying that my hand luggage would be deemed too large and forcibly stowed. Then I boarded my buzz rattle flight, hoping for an empty seat next to me. No luck. It was to be the passive aggressive dance of the armrest elbows all the way. I chose the chicken curry for lunch. Because the rules of daytime drinking are relaxed in the air, I opted for a glass of white wine.